THERE THERE | Working Remotely on iPhones

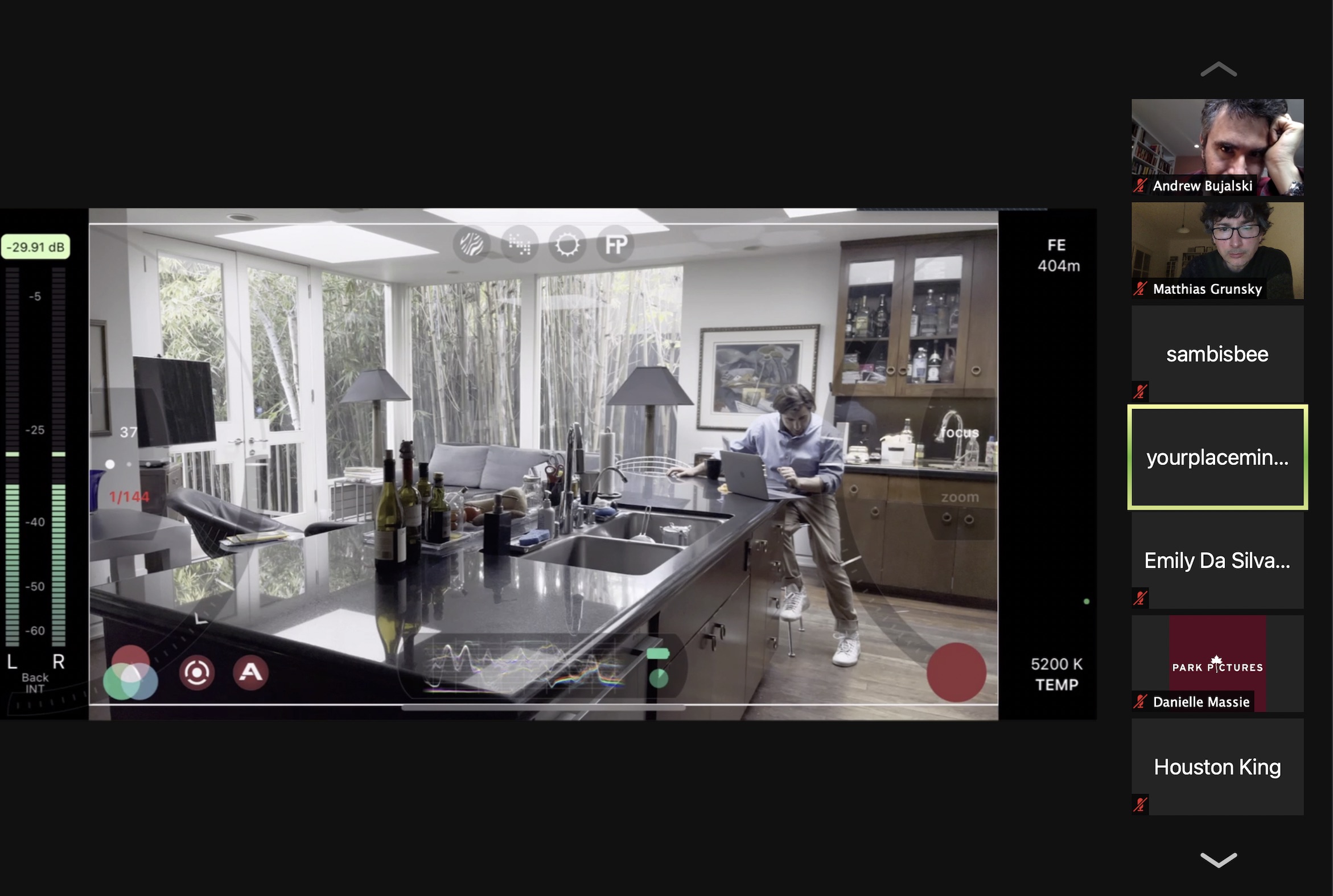

the Zoom screen as our video village

I have been behind the camera on all of Andrew Bujalski's movies, and THERE THERE is our seventh collaboration. I love how Andrew challenges me with a new approach to tell his stories every time. We shot his first films on 16mm negative in color and in black and white. For the movie COMPUTER CHESS, we moved away from film for the first time and worked with an old black and white video tube camera made in the seventies—the craziest of Andrew's technical ideas back then. After the two following movies on conventional digital ARRI cameras, Andrew conceived THERE THERE in the middle of Covid with perhaps his most radical technical approach yet.

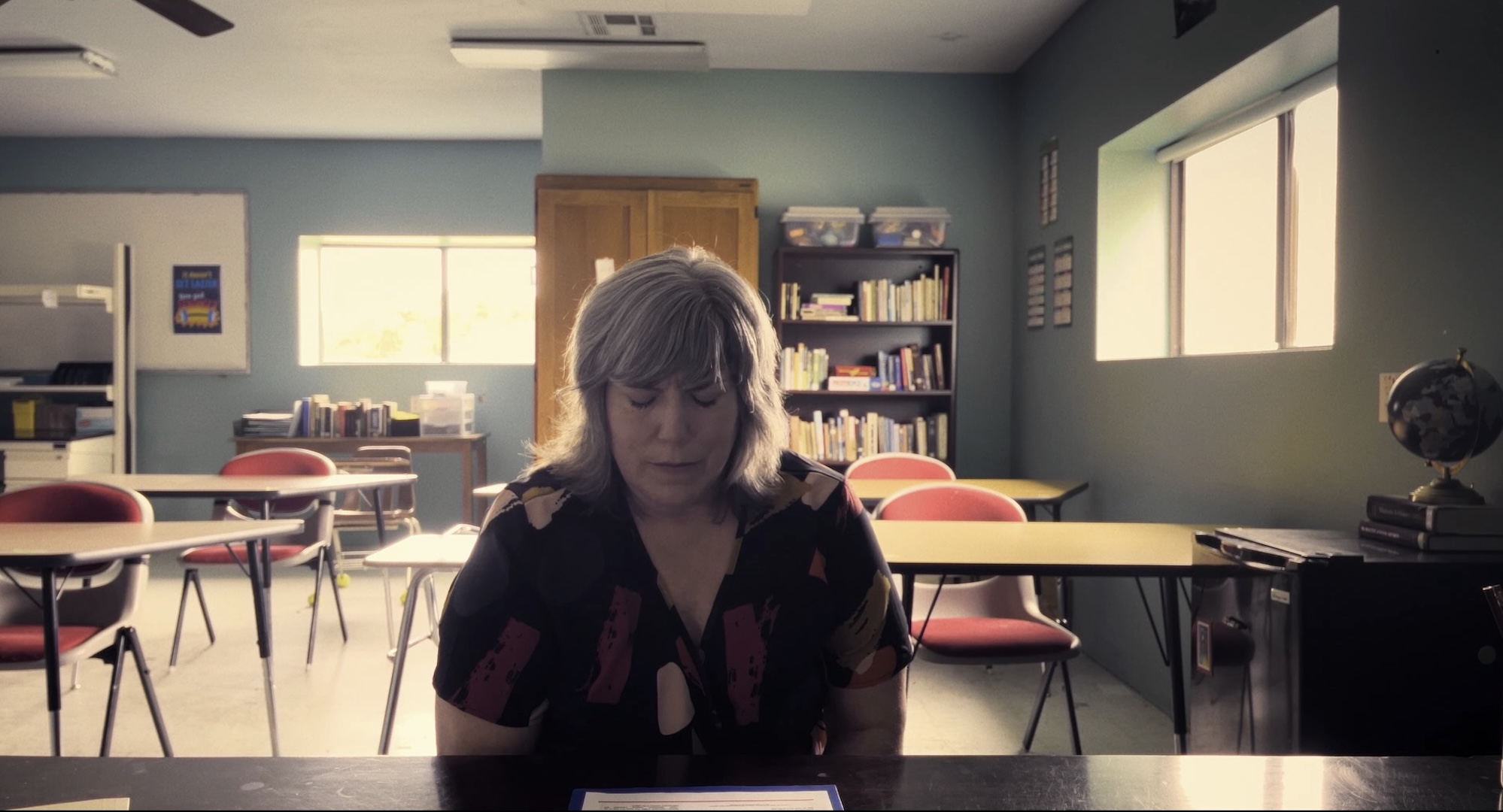

Molly Gordon

FORM REFLECTS CONTENT

When Andrew told me about his idea for THERE THERE and how he wanted to shoot it, I got eager to dive into this new challenge. It made a lot of sense to me to tell this story, which has so much to do with emotional distance between people, in a way where the actors and filmmakers actually never were in the same room together. The idea was to film this story without Andrew or me ever being on set, with the actors never seeing their counterpart, each one of us isolated in our own room, often thousands of miles away from each other. Each location in the script consisted of at least two different real locations. The scenes were shot weeks, sometimes even months apart. The characters in this movie are trying to be connected but are not really succeeding. Having them shot in different locations made a lot of sense to me to support that dilemma. This method became a mirror of the story's themes—isolation, miscommunication, the struggle to bridge distance.

Roy Nathanson

NEVER IN THE SAME ROOM

Films are about tricking the audience. It's the magic of filmmaking that the brains of the audience want to believe and connect things that are not really connected but suggest that they are. Even 24 frames making a second of fluent movement—each one of them is really just a still image. In THERE THERE, we took this fundamental principle of cinema and made it explicit: two people who were never in the same room, filmed months apart, would appear to share intimate moments together. We wanted to keep everything as small, simple, and isolated as possible. So we ended up with just another actor in the room off-screen to shadow act as the counterpart, and a local camera assistant, who set up the camera, our occasional few lights, and microphones. This minimal crew reflected the stripped-down, intimate nature of the story itself.

our standard camera setup

THE TINY SENSOR

We brainstormed which camera to use, and considering all the aspects of our reality, we decided to work with smartphones and bought several iPhone 12 Pro Max models. They are small and easy to use, and compact enough to ship around the globe. But more importantly, the iPhone felt right for this story. In a film about people trying to connect across distance through technology, using the very device that has become our primary tool for remote communication felt deeply appropriate.

Of course, shooting a movie remotely on tiny smartphones posed some challenges to me as the cinematographer. I did not want to make the iPhone image not look like an iPhone image, but instead embraced the look of the small sensors and lenses. They result in huge depth of field, making everything sharper than we are used to see in a cinema. Besides the character of the iPhone image and the compression artifacts, the image does get noisy pretty soon in the shadows and in low light situations, which were unavoidable in our circumstances. These technical limitations—the noise, the compression, the unforgiving sharpness—became part of the aesthetic language of the film. They reminded the viewer, perhaps subconsciously, of the mediated nature of all connection in our contemporary world.

But I had to constantly check if we were going too far, making sure that I was able to control the image from far away as precisely as possible while still embracing the inherent character of the medium.

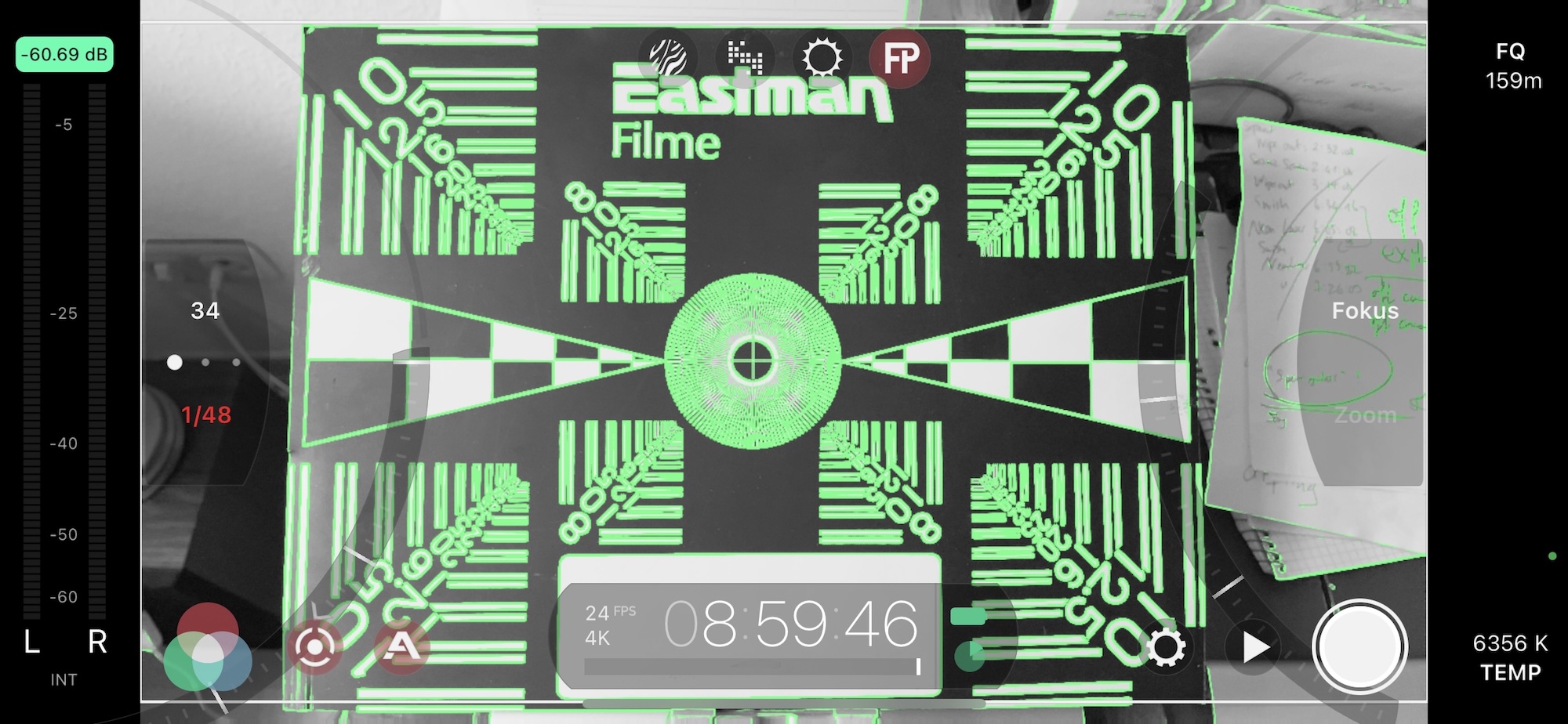

focus chart as seen on the iPhone in the FilmicPro App

APPS AND THE INTERNET

Luckily I found the Filmic Pro app in my research. It was essential and the only way for me to set exposure, focus, and color temperature in the way I wanted. Especially on the sometimes fuzzy and delayed image over Zoom due to changing internet speeds, the interface of the Filmic Pro app was truly essential. It showed me a waveform, the set exposure, color temperature, and focus at all times on the mirrored iPhone screen. I had precise control over these settings to match our shots, from all the different locations. Together with Brandon Thomas at our post house, TBD in Austin, we tested different ways to make it all work through the whole post process. Although we wanted to end up with a 2K master, we shot in 4K to have all the color depth the iPhone could give us in the grade. We chose the 10-bit "LogV3 Filmic" setting, recording in H.264, which gave us the best base.

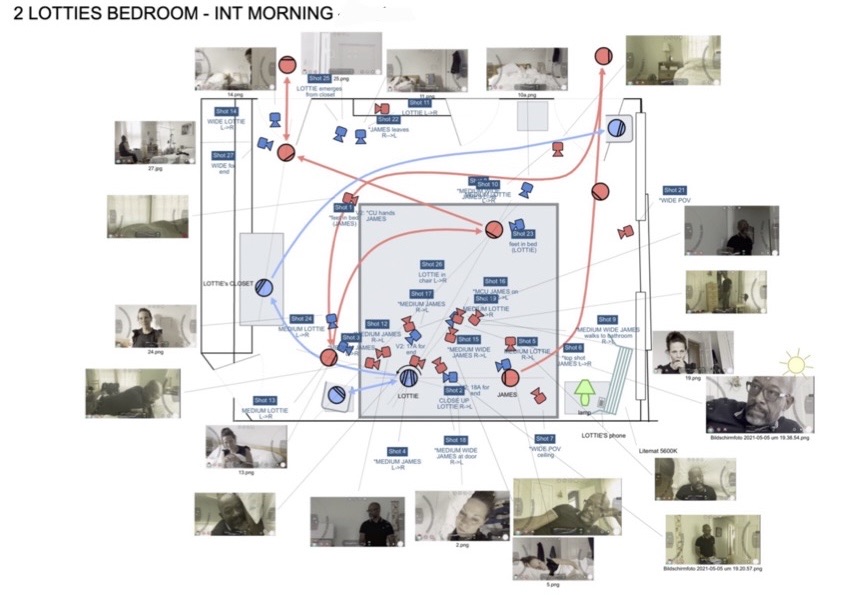

a diagram of the first scene with stills from the blocking rehearsal

PLANNING FROM AFAR

The biggest challenge for me was to plan our shots on the different locations without ever having been there. We discussed our location options by going through photos from our local location scouts. Once we had decided on a location, I started drawing sketches based on the pictures. Then I talked through each scene with Andrew, also on Zoom, screen-sharing drawings and photos, and we planned our shots. I put camera angles into my floor plans and then did the same on the reverse angles on the corresponding location.

Although we had minimal equipment, I had to order certain things specific for each location and scene. Sometimes it was an umbrella to block the sun and create soft overhead lighting, an LED strip light to visually connect our three bar locations, sometimes a spotlight or other lamps, a curtain—it was all very simple, but had to be specific. Every choice had to be deliberate because there was no room for on-set improvisation when the "set" was thousands of miles away.

Annie LaGanga

THE PROCESS

We filmed the scenes with Jason Schwartzman first. He had the great idea to do a blocking rehearsal the day before shooting a scene. While it was gret for Andrew and the actors to go through the scene, it was also very helpful to figure out if our visual plan worked. We ended up using that system for all the scenes. We set up each shot one after the other on those rehearsal days, adapting our framing and sometimes finding out that we were missing a prop or that we could improve things by buying another lamp etc.

The filming process was as intense and stressful as it feels when being on set in person. Sitting in my apartment mostly throughout nights, since I was six to nine hours ahead in my time zone here in Munich, I had multiple computer screens running, on which I had the script, the shot lists, the floor plans, the corresponding stills from the other side of scenes we had already shot, and the Zoom screen, on which I had the iPhone's mirrored screen from set and through which I communicated with Andrew and people on set.

It felt like shooting underwater, where things also are cumbersome and delayed. Andrew had to direct the actors with the time lag through the internet in mind. Sometimes when I told an actor to move a bit in one direction, they were already somewhere else, but I didn't see that yet due to the delay. Also, it's impossible to read facial expressions and other small things, which are such a big part of our emotional interaction, and filmmaking is all about emotions in the end.

This disconnection was frustrating, but it was also strangely perfect. We were experiencing firsthand the very thing the characters in the film were experiencing—the friction of trying to connect through technology, the lag between intention and reception, the way nuance gets lost in translation across digital space. The production became a performance of its own themes.

We saw less on Zoom than what we actually recorded due to the lower resolution. Therefore, I watched downloaded dailies the next day with even more anxiety than on other movies. The process demanded a lot of patience from all of us on all sides of it.

Molly Gordon

EMBRACING THE LIMITATIONS

What struck me throughout the production was how the constraints we faced—the iPhone's sensor limitations, the Zoom delays, the impossibility of being physically present—weren't obstacles to overcome but rather elements to incorporate. In traditional cinematography, we often work to hide the technology, to create the illusion of unmediated reality. In THERE THERE, the technology itself became visible, became part of the story. The slight noise in the shadows, the characteristic depth of field of a phone camera, the compression artifacts—these weren't flaws to apologize for but honest evidence of how the film was made, and by extension, how we live now.

This project reminded me that cinematography isn't about creating beautiful images with the best equipment. It's about finding the right visual language for each story, even if—or especially if—that means working with tools and methods that seem impossible at first. Sometimes the limitations we face don't diminish the work; they define it.

Matthias Grunsky