LEIBNIZ - CHRONICLE OF A LOST PAINTING

"The Truth in the Image" | Notes on Visual Design

with director Edgar Reitz, producer Ingo Fliess, actor Edgar Selge

WORKING WITH EDGAR REITZ

When I was asked to serve as cinematographer on a film by Edgar Reitz set in the Baroque period and confined to a single room, I felt honored, but also had great respect—perhaps even some fear—about the task ahead. However, from our very first meeting, this transformed into enthusiasm. All the ideas and philosophical thoughts about the film that Edgar explained to me resonated immediately. It was as if we had known each other for a long time. Perhaps this has something to do with the fact that since childhood, I had deeply admired the work of Edgar's longtime cinematographer Gernot Roll. Perhaps his way of crafting film images had written itself into my subconscious.

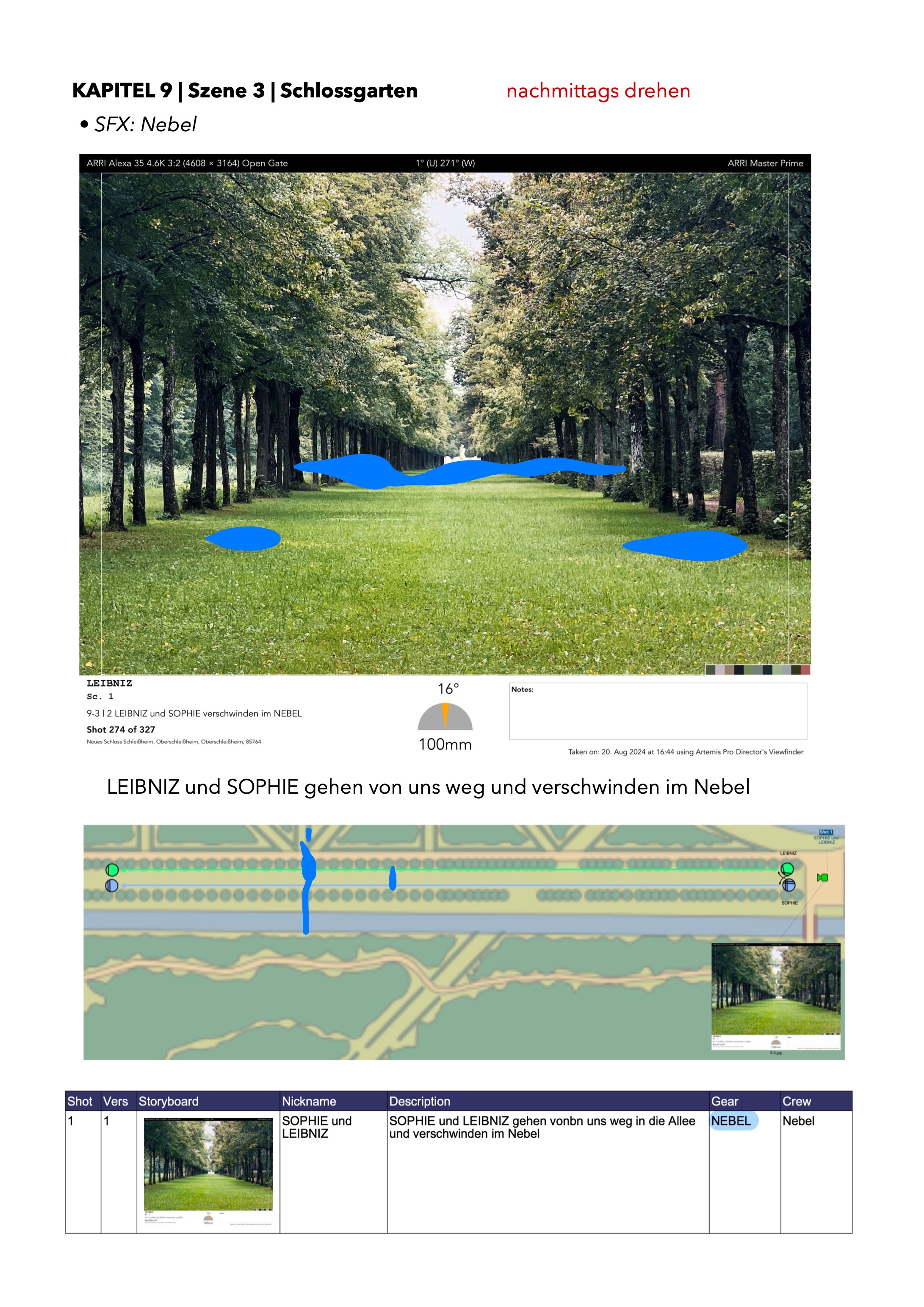

notes for the final scene

PREPARATION

Planning a film is always complex. The various elements can quickly take on a life of their own and spiral out of control, whether through conventions, habits, or the usual limitations of time and money. For this reason alone, it's always crucial for me during preparation to sense as precisely as possible how the director wants to tell the story. A clearer and clearer picture and feeling about the film develops in the process, but of course it only truly comes into being once you start shooting. During the shoot, however, you're under time pressure and must solve many problems at once. You must then be able to draw instinctively on the ideas and concepts from the preparation period. Since this was my first collaboration with Edgar and I came to the project relatively late, every impulse was very important to me, and I absorbed all of Edgar's thoughts like a sponge.

Before shooting began, I had accumulated a large collection of notes with concrete ideas and concepts, including rules we had established. Some of these rules were meant to be broken later. But the process of thinking them through was important in order to then overturn them. In general, this exchange of ideas doesn't necessarily have to lead to a fixed plan; rather, it provides the foundation for creativity during the shoot. Edgar loves spontaneous decisions, and as stressful as they can be in the moment, I ultimately found new creative decisions on the shooting day very invigorating for the film. But these only worked because we had tried out and discussed so much during preparation. Even being present at the read-throughs with the actors helped me enormously as a cinematographer. I not only got to know the actors and Edgar's way of staging, but also the motivations behind his decisions. Step by step, I penetrated deeper into the film in Edgar's mind.

Edgar Selge as LEIBNIZ and Aenne Schwarz as AALTJE VAN DER MEER

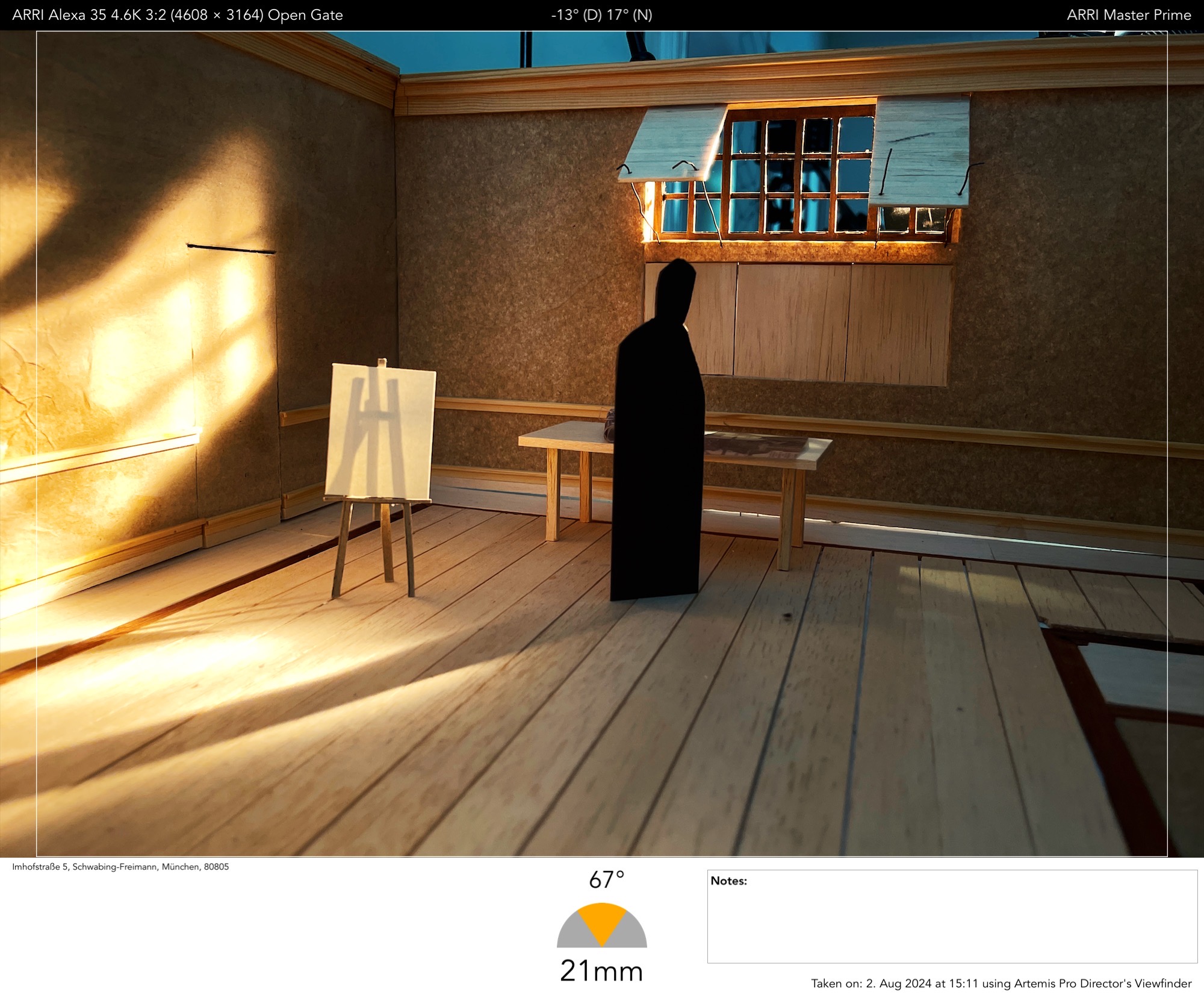

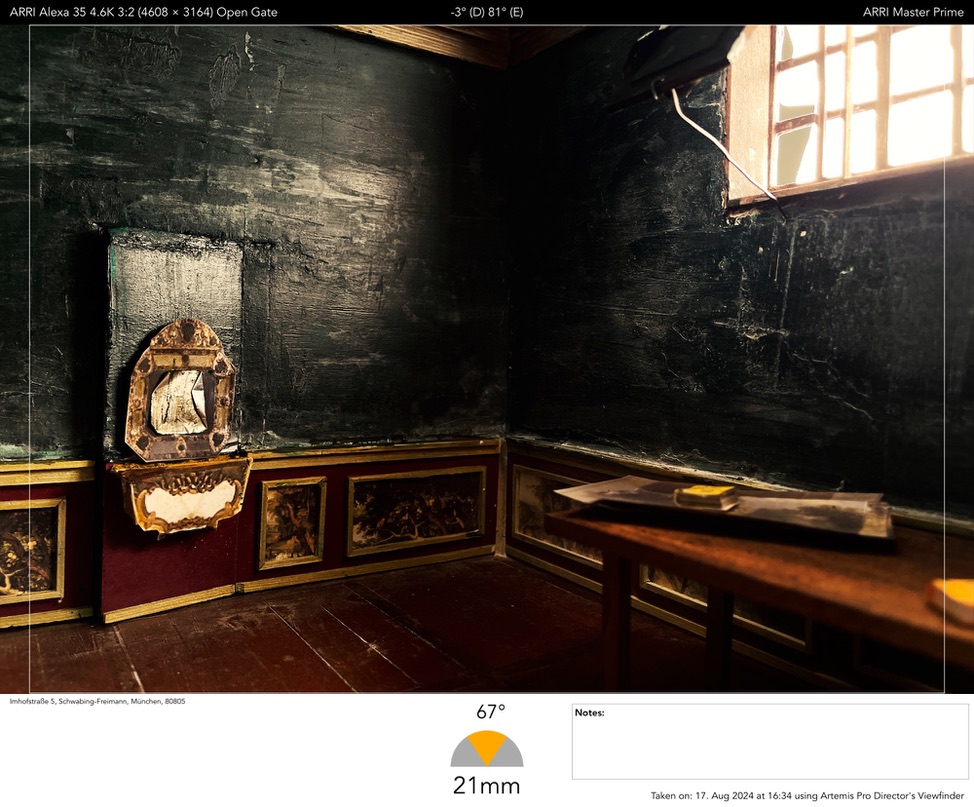

THE CHIAROSCURO CANVAS

Chiaroscuro, the painting technique that appears in the screenplay and into which we wanted to place our LEIBNIZ world, involves the technique of depicting strong light-dark contrasts. In a certain sense, we wanted to give the cinema screen a dark chiaroscuro primer, painting from dark into light, as Aaltje says in the film. If it had been an option, I would have suggested shooting on film. The organic way film emulsion reacts to light and reproduces colors would have fit this concept well. Since that wasn't a realistic option, I experimented at an early test two months before shooting began with a very contrasty look with muted colors for our digital ARRI camera, the Alexa 35. I also pushed the color of the light very much into yellow-orange, referencing certain Baroque paintings. I wanted to go to extremes stylistically and technically right from the first test, creating a kind of uncompromising naturalism. Edgar and I immediately liked the look very much. This test laid a helpful foundation for how far we could and wanted to go with contrast, the depth of black, and color.

Barbara Sukowa as SOPHIE

ACADEMY FORMAT

From the beginning, Edgar and I both felt that the Academy format with its 1.37:1 aspect ratio was right. The faces in LEIBNIZ should dominate the frame, and they can do this better in this format than in a wider aspect ratio, where the background or foreground often weakens the presence of the characters and makes them smaller. In portrait painting, one naturally finds mainly vertical formats, which also spoke in favor of the taller format for us.

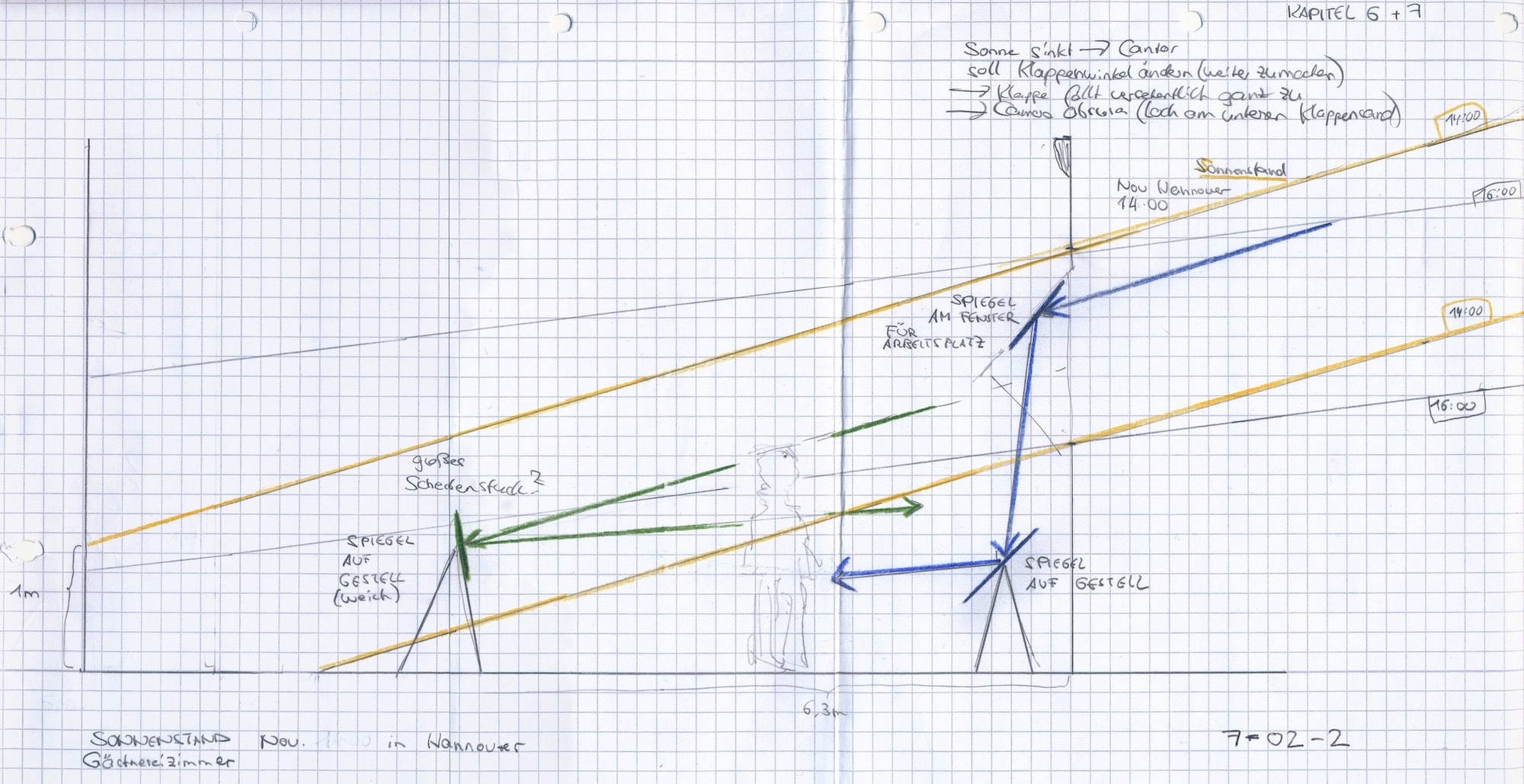

simulating the moving sun light

the miniature model by production designer Renate Schmaderer

SOUND STAGE CONSTRUCTION

Edgar and I weren't enthusiastic about the idea of shooting an entire film on a sound stage. For practical reasons, however, there was no alternative. Working in a sound stage brings many advantages: independence from daylight and weather, or the ability to remove wild walls for certain camera angles. But a studio build also carries the danger of lacking real life. The possibility of building the room exactly as you want it is of course initially wonderful, but it can also very quickly appear like a theater stage where everything is too perfectly tailored to the action.

In any case, we deliberately built certain restrictions into our construction in order to transform them into creativity, as one would have to do with any real location. For instance, we consciously had only one elevated window in our gardener's room, as we had seen in drawings of Baroque painter's studios. Working with production designer Renate Schmaderer, we developed the room using a model and drawings. With small lamps and model figures, we simulated and photographed the movement of light in front of the window. While computer simulations now exist for such purposes, a real model feels completely different—you sense real textures, and it feels more alive than a smooth, perfect computer simulation.

After we had made all the decisions for our gardener's room, where we would shoot the entire film, it got exciting. The room was then built in a few weeks according to the plans, and apart from small corrections, there was no going back. During the construction phase, I was able to shoot initial tests in the studio build, which was important for further decisions, such as the exact color tone of the walls. All of this flowed seamlessly into the rehearsal week with actors in costume, during which I shot additional tests in parallel to refine the look.

lighting sketch for scene where Aaltje lights Leibniz with mirrors

THE CALLING OF ST. MATTHEW | Caravaggio, 1600

A flare in the Leica Summilux-C, showing the origin of the camera obscura projection: a tiny hole in the window shutter.

LEARNING FROM BAROQUE MASTERS

Baroque paintings and the light within them already play a major role in the screenplay, and for our style of telling this story, Baroque painting was the most important guide. After the first conversations with Edgar, I studied art books and paintings. Particularly in the images of Caravaggio, one finds a great deal of contrast. I was especially interested in the light direction and the fall off into darkness. The proportion of black in chiaroscuro style images (chiaro stands for light and scuro for dark) often takes up a dominant share.

As mentioned, this one elevated window in our studio build was our only main light source throughout the entire film. It was important to me to play through the course of the day and different weather conditions to give each scene its own particular character. We therefore had different light sources in front of the window, sometimes lighting directly, sometimes indirectly, depending on the imagined weather and time of day. In some situations, we also let a cloud pass in front of the sun during the shot or showed the path of the sun across the sky in an accelerated way. We realized this by dimming, changing the color temperature, and moving our "sun spotlight" on a crane arm. LED lamp technology has developed rapidly in recent years. The new LED spotlights were perfect technology for our concept due to their lightness and especially the ability to remotely control their color temperature and brightness precisely and gradually.

I wanted to vary the color abd quality of the light in LEIBNIZ over the course of the story and times of day, always within a color space that felt like a painting but not unnatural. This ranged from warmer, wintry hard sunlight to overcast days with somewhat cooler and softer light. For the dramatic tension and oppressive sadness that subtly increase toward the end of the film, I gave a slightly greenish fill light, a color tone I had seen in paintings by Vermeer.

The scenes in which Aaltje experiments with light for her painting were already so well described in the script that I had a precise image in mind. Beneath the surface these scenes are about filmmaking, as many other moments in LEIBNIZ. For the implementation of the mirror scene, which is also about enveloping light direction, I had made an almost mathematical sketch to scale of our build. The positions and angles of the spotlight and mirrors in relation to the window had to be arranged so that Aaltje's lighting design would work.

Transforming the gardener's room into a camera obscura for a fleeting moment was an idea I found very beautiful from the first reading of the screenplay. For this, I tested a pinhole lens early on. I shot footage of trees against the sun, which we then projected onto the actors with a high resolution video projector.

During discussions about the numerous props, some of which suggested scientific experiments, we had additional ideas for lighting effects. For example, I had experimented with a prism that breaks light into its spectral colors. Shoemaker's globes were also a beautiful light prop. Shoemaker's globes were used by craftsmen to focus candle or sunlight onto their workspace. They are glass spheres filled with water that function as a converging lens. In one of my tests, I directed light through the prism and a shoemaker's globe in which the water moved slightly. We liked this test so much that we incorporated it into a few scenes as a magically wondrous effect. Perhaps these are moments when logic, reality, and the inexplicable collide.

dolly grip Simon Arevalo Saint-Jean

CHOREOGRAPHING THE CAMERA

One reason I felt so aligned with Edgar was that he thinks very visually and, like me, has a tendency to move the camera. Edgar never wanted to fall into a conventional editing sequence where you shoot a wide shot and then close-ups. Each shot should stand on its own and be explicitly designed for the respective moment of the narrative. Often in scenes with long dialogues, we gave the actors motivations to move through the space, and choreographed the camera movements with them so that the individual moments of the scenes received the strongest camera angle. While this required many rehearsals, we often had the entire scene in the can in one shot, only needing to emphasize one moment or another in an additional shot. Longer passages in a moving shot thus created a natural dynamic flow.

Edgar Selge as LEIBNIZ

FACES

The actors, or rather the characters they play, are the center of every film for me. In LEIBNIZ, the faces are perhaps even more essential than in other films. After all, it's also about painting a portrait. And so many things could happen in the faces of our actors that it was a joy to capture them. Here too, Edgar was very precise in his staging to properly dose the expression for the screen.

The choice of lenses was very important to me in this context. We tested several lenses and then decided on the Leica Summilux series. They are contrasty and have a beautiful fall-off into blur. Our favorite lens for portraits was the 35mm. It gave us a natural viewing angle on the characters at a distance that felt equivalent to that in the paintings.

Having the freedom—or even the mandate—to model the faces with the means of chiaroscuro light was great fun. There are so many nuances that can push the expression of the human face in a certain direction, such as soft or hard light, or the light angle, which I usually set steeper here. One could say that Edgar, through our shared understanding of the visual style of our film from the very first test, motivated me to dare greatly.

Matthias Grunsky